What does responsible mean to you? First, know yourself.

(Third in a series on responsible investing)

Very often, ethically conscientious investors cannot themselves describe unambiguously what they do and do not regard as responsible investments. That, as I wrote in my introduction to this series, is the second most important reason why responsible investing can be so difficult. This situation, of course, creates challenges for financial advisors and for the financial services industry generally. How is an adviser to satisfy a client’s expectations if the client cannot explain these? Even if an investor chooses to manage his or her own responsible portfolio, it is still logical to begin by defining what he or she regards as responsible and not responsible, as well as what one hopes to achieve through investing conscientiously.

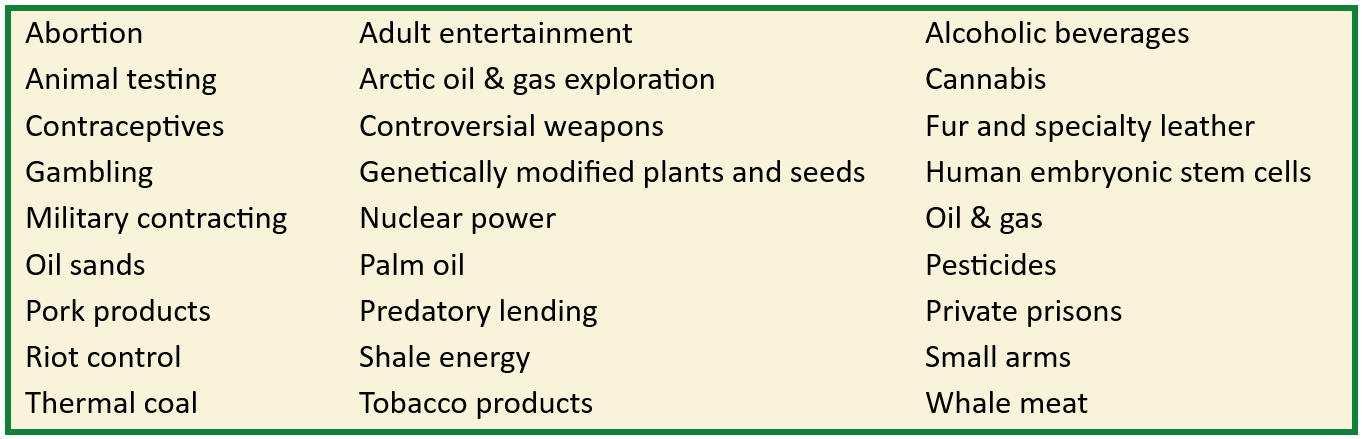

Responsible investing comes in many flavors. Consider, for example, the “Product Involvement Areas” that Sustainalytics considers in its ESG screening processes:

That seems like a pretty good start as to products and services that people could object to, doesn’t it? But, without missing a beat, I’d add single-use plastics, auto fuel from food crops, sugary drinks, bottled water, fast fashion, disposable electronics, and coffee pods. And that’s just getting me started.

Moreover, most responsible investors – at least when they think about it for a while – are concerned about more than just a list of objectionable products. Remember, for example, that “ESG” stands for environmental, social, and governance. The “E” gets into issues like climate change, deforestation, pollution, biodiversity loss, habitat destruction, and more. The “S” takes in gender equity, workplace health and safety, community relations, charitable giving, and a bunch of other things. The “G” includes, among others, matters of shareholder rights, executive compensation, board diversity and independence, and audit practices.

Almost certainly, not every product or issue covered in the Sustainalytics list shown above will be important to you. If you’re a staunch Roman Catholic or a fundamentalist Protestant, for instance, you may care a lot about abortion, contraception, and stem cells. If you’re not, these may not be major issues for you. For Muslims, pork products, alcohol, and predatory lending might be very important. Sustainalytics understands that these differences exist. Its aim is to help specific investment clients to screen according to their own preferences.

I think it is interesting to note, by the way, that religious organizations were among the first to engage actively and formally to promote responsible investing. Quakers, Episcopalians, Methodists, Muslims, and Roman Catholics appear to have been leading denominations in this regard, but this has become much more ecumenical and sophisticated in recent decades. For instance, The Interfaith Center on Corporate Responsibility, or ICCR (www.iccr.org/), was founded in 1971 to pressure corporations to divest their investments in South Africa and to stop doing business there until the racist system of apartheid would be ended. Originally a pioneer in shareholder activism, the ICCR is today a coalition including member organizations from many faiths and it works actively on issues of climate change and environmental justice, health equity, corporate political responsibility, worker justice, and more.

Spell it out for yourself

Because the range of views on corporate responsibility is so broad, I think the best starting point for an individual (or couple or grouping of some sort) is to spell out for yourself what issues are most important to you. In addition to a prohibited or disfavored products and services list somewhat like that above, I suggest taking what can be called a “stakeholders” approach. Stakeholders are groups or entities potentially influenced by a company and its activities or that are able to affect such organization. (I’m going to assume, by the way, for purposes of this discussion that we are considering stock investments in exchange-listed companies. Although these are the most common investments, there exist numerous other investment possibilities, too.) The table below lists (in no particular order) the most commonly cited stakeholder groups. It also states by way of example some of the important issues typically involved. This is far from being a comprehensive summary, and I’m not going to fill in all the details in the “What concerns me” column, because people should not need for me to tell them what they care about.

There are many resources available on the internet that address these subject areas, and I suggest you spend some time on background reading to stimulate your thinking. Search for terms like “ESG investing,” “sustainable investing,” and “corporate social responsibility” to get started. Once you have completed a table similar to the one shown above, you will have a clearer understanding of what is and is not important to you personally and you will have a basis for evaluating and comparing potential investments. Your table might contain fewer items, more items, different items. You might develop this into a checklist of your own for ticking off the acceptability or non-acceptability of specific issues or even a relative scoring matrix.

I want to interject here with a specific piece of advice: When you create your own table, save it to a dedicated directory on your computer or server so that you have a permanent record. You can come back and add to, subtract from, or annotate your table at any time. As I will describe again in this series, I have a dedicated directory structure where I keep notes on nearly all aspects of my investment strategy, stock research, and portfolio management. I encourage other responsible investors to do the same. That way, you can be more consistent in your approach and be reminded of what you did and decided in the past and why.

A future essay in this series will provide guidance on how to find, interpret, and utilize information presented on these issues. In the meantime, let me share just a couple examples of how I interpret this information and use it in making investment decisions. I should note that I do not strictly use a best-in-class selection process (described in my previous essay in this series). For me, social responsibility (a general term I prefer to use that encompasses ESG and sustainability) is pretty much of a binary yes–no screen. If a company passes through my social responsibility screen, I then evaluate its investment attractiveness by means of what is termed fundamental analysis. I will write more about my approach to fundamental financial analysis in a future essay.

An example: United Natural Foods

I want the companies into which I invest to treat appropriately all the relevant stakeholders, and among those I also do not want them to forget about me. As an investor, I’m a stakeholder, too. This is top of mind when I think of United Natural Foods (UNFI), one of the companies whose shares our small investment partnership holds. From its founding in 1976, UNFI has been a distributor of natural, organic, and healthy foods. Since acquiring SUPERVALU, another large distributor, in 2018, it has become more of a general grocery distributor and it is today the largest wholesale food distributor in North America.

UNFI has extensive reporting in the sustainability section of its corporate website and a good track record of looking out for labor, communities, consumers, suppliers, the planet, and others. Although I like all that, my sense has always been that providing great returns to us shareholders is not such a high priority at UNFI. The company’s share price today is about at the same level as it was 20 years ago, and UNFI doesn’t pay dividends. So, if somebody had bought the shares two decades ago and held them, he or she would have earned zero returns in the interim. Nevertheless, the share price has at times been twice as high as it is today and at other times only a fraction of what it is now. As of this writing, our partnership has an 82% average capital gain on our UNFI holding, but that’s because I only buy the shares when developments within the company or its market environment cause the share price to fall sharply.

In UNFI’s case, I think it fair to say that on balance this is a responsible company, but, its 2018 debt-financed acquisition of SUPERVALU that put the company deeply into debt arguably was not in the shareholders’ best interests.

A lesson I suggest be taken from the UNFI example is that responsible investors should not buy stock in a company just because that organization does nice things, like support regenerative farming, use electricity-powered delivery vans, and reduce food waste, all of which, to its credit, UFNI does. (Sustainanalytics gives UNFI an excellent ESG Risk Rating score of 17.7, which means “negligible” risk.) You also need to think of your potential for investment returns. I’ve looked at many companies that seem to be doing nice things but that, upon even initial analysis, I find to be not investable. A good example is Hain Celestial Group (HAIN).

I looked at HAIN back in 2016, when I was doing the first research on companies whose shares potentially might be included into our new partnership’s portfolio. I still have my notes from that time, wherein I wrote: “This is a company that probably is in a lot of trouble. It’s got some good brands. It is the American publicly traded leader in the natural and organic business. My guess is, though, that although Hain is offering things people want, people don’t want to pay the higher prices to obtain them… I think it needs to consolidate and adjust its strategy; then, if it doesn’t go bankrupt, and if (the stock) is cheap enough, it could be interesting.”

Since that time, the HAIN share price has fallen by about 95% and, fortunately, I never bought the stock. I don’t use this as an example to show how clever I am, because I have more than a few times lost money on individual stock positions through the years and made at least my fair share of investment mistakes. Rather, the lesson here is that we should not invest in things solely because they give us nice feelings and tick off a lot of the ESG boxes. We still need to analyze them for their potential to generate investment returns.

In the end, I chose to invest into UNFI under certain conditions even though I felt its treatment of shareholders was borderline responsible at best. It squeaked through my responsibility screen. HAIN never got a full social responsibility review from me, because it looked like a losing proposition from a financial perspective.

An example: Utah Medical Products

Investing, like life generally, is not necessarily simple, so I will take a look now at a perhaps thornier example. Utah Medical Products (UTMD) is tiny relative to most other companies on the U.S. stock exchanges. It produces and sells disposable and reusable medical products especially in relation to the needs of women and babies.

When I first looked at UTMD in early 2017, I wrote in my notes: “The pluses are that it is a consistently profitable (30% profit margin, 17–18% return on equity) company that is a regular dividend payer, has no debt, has plenty of cash, and has a low beta. (Note: Beta is a measure of risk.) It has no significant lawsuits against it. It looks like a reasonably good candidate for a private equity or other takeover…This seems to be a very conservative company. The CEO and Chairman is 70 years old and the board is probably made up of his buddies (Note: my personal guess from the time, which may or may not be true).”

Utah Medical falls into “medical technology,” one of the six sectors within which I invest exclusively (more on that in a future essay). Inasmuch as it is a small company, I did not hold UTMD to the same high standard on responsibility criteria that I would a larger company. For example, it does not produce a fancy sustainability report. At the time of my initial research, I could find no evidence of issues or problems concerning UTMD in the available materials issued by the company or by searching the internet. I like its emphasis on mother and baby health. The management likes to stick to its knitting, so to speak, and generally does so.

More recently, some issues have come up. The company now faces a host of lawsuits in relation to its Filshie Clip female surgical contraception devices, the elderly CEO is still there almost a decade later, the average age of the directors is 78 (with members range from 66 to 87 years of age), and the CEO has become outspoken in his defiance of “WOKE” shareholders, “political correctness,” and DEI (an abbreviation for diversity, equity, and inclusion).

“With respect to DEI,” the CEO wrote a year or so ago in a report to investors, “although a large majority of Company employees are non-white, they have been employed for their skill, work ethic and commitment to the Company’s objectives, nothing else. With respect to the board of directors, we do not seek diversity, however defined. We appreciate individuals who have high integrity, business savvy, an owner-oriented attitude, excellent experience and education, and a deep genuine interest in achieving the Company’s objectives.”

Despite the CEO’s cantankerousness and the Filshie clips litigation, the latter of which I have investigated and found to my satisfaction not to constitute a problem of irresponsible actions by the company, the board has clearly done a good job of running Utah Medical. Setting age and other aspects aside, the board members individually and collectively are highly qualified. Although the litigation does newly pose a substantial risk and the share price is now quite depressed, I recently resolved neither to sell nor add to our position.

Knowing what I know now, perhaps I would not make an initial investment into UTMD today, but I went into this investment back in 2017 with eyes wide open. The company is a little quirky, communication is pretty transparent, and management does not go out of its way to polish its own apple. By the way, the CEO has wisely avoided making any more controversial statements in recent months. Is Utah Medical a responsible company? Well, I don’t agree with the CEO’s views on some things, but, so far, I have no justification to say it is not responsible in its actions. The litigation is a concern, but, from my understanding, this is not a responsibility issue even though it surely is an important matter in regard to whether we do or do not continue to hold the shares.

The UTMD story offers a couple lessons: When it comes to responsibility, companies and their managements should be judged by what they do and not by the spin that the public relations and marketing people put on things. Small companies should not be evaluated too harshly just because they do not produce slick sustainability reports. Remember from my previous essay, even the world’s largest cigarette makers can manage their images to look like corporate saints. Regarding the age of the board members, should we view the fact that older board members are not replaced as irresponsible governance or is this a positive indication that age discrimination is not practiced at this company?

Using the Sustainable Development Goals

We all have our own moral views and can generally recognize right from wrong when we see it, but, when it comes to investing, I find it useful to have a general framework to guide my thinking and reinforce my personal discipline in this regard. Personally, I find ESG conceptually to be a little out of step with the times and somewhat discredited as a guide to responsibility assessment. I prefer to use the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals, or SDGs, to provide structure and substance to my thinking on sustainability and responsible investing. Adopted by all United Nations Member States in 2015 in support of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, the SDGs consist in a set of 17 goals that concisely identify and summarize crucial social, economic, and environmental issues and point the way toward a potentially better future. We at BlueGreen have created a handy reference to the 17 goals and their 169 subgoals, or targets, at the BlueGreen website. Feel free to download a copy for yourself by clicking below.

In addition, the United Nations provides a great deal of information about the SDGs. Increasingly, companies are setting their own sustainability targets in terms of the SDGs. I encourage everybody interested in responsible investing to well familiarize themselves with the SDGs.

What are your returns expectations? Your risk preferences?

At the beginning of this series, I stated my opinion that people who care what their invested funds support and do not support should put their money into what they want to and not invest into what they do not want to. That may, but need not necessarily, result in lower expected or actual returns. In addition to financial returns, by the way, every investor should consider, too, how much risk he or she wants to bear. This is an aspect of investing that sometimes does not get the attention it should. I’ll have more to say about that in a future essay.

So, you should ask yourself, will you be satisfied only if your returns match or exceed those of a low-cost S&P 500 Index fund? What about if you earn 90% as much as the low-cost S&P 500 Index fund? What about 80% as much? Quite possibly, the S&P 500 will not at all be an appropriate benchmark against which to judge your own performance. How would you rate your potential fear of missing out – so-called FOMO – against your desire to do good?

There are plenty of other benchmarks. Let’s look at an example. Standard & Poor’s has reformulated its basic S&P 500 into a wide range of variants. One of these is the S&P 500 Scored and Screened Index (SPXESUP), formerly named the S&P 500 ESG Index. According to S&P Global, it is “designed to measure the performance of securities meeting sustainability criteria, while maintaining similar overall industry group weights as the S&P 500®.” This index might or might not meet your ethical criteria. It won’t meet mine, by the way, but I’m not you.

On a 5-year basis, as of this writing, the SPXESUP has yielded a 5-year total return (inclusive of price gains + dividends but with no fees deducted) of 13.91% versus the regular S&P 500’s total return of 15.76%. Thus, the ESG index returned 88% of what the wholly agnostic index did.

This is just one example among dozens of potential benchmarks I might cite. Some will underperform in some periods, outperform in others. The main point is that the responsible investor should think about expectations and, if he or she has a financial adviser, discuss them with that professional.

In my own investments, I pay close attention to sustainability and corporate responsibility, to expected and actual returns, and to the level of risk, including both the specific risks of individual investments and the overall level of risk in the portfolio. The small portfolio that I run for myself, family and friends is, in my view, much more responsible than is the socially agnostic S&P 500, it has lower risk (as measured by the standard deviation of its monthly returns relative to those of the index), and is limited to just six investment sectors. I personally use a composite benchmark that is just 25% based upon the S&P 500, but I’ll have more to say on that in future. Relative to my chosen benchmark, which I have tracked for several years, I can say that I do not want to give up any return over the long term. Since inception, I have beaten my composite benchmark pretty consistently, but not usually the S&P 500.

How flexible are your ethics?

If some sector or group of stocks has been really hot recently and you’re not invested in it, your investment returns are likely to underperform. Lately, the market’s hot spot has been artificial intelligence, but in future it might be nuclear power, weapons systems, human cloning, surveillance systems, or something else. Ask yourself, will you be willing to sit out those loftier returns? If not, well, that’s up to you to decide, but you might want to think about it ahead of time.

Particularly in the past couple years, as the so-called Magnificent 7 (i.e., Alphabet, Amazon, Apple, Meta, Microsoft, Nvidia, and Tesla) and a few other artificial intelligence and technology stocks have increasingly been overweighting the major indices to a place of extreme skewedness and strongly driving them skyward like Icarus on his waxy wings, it has been practically impossible to match the S&P 500 without investing into those few companies. I will never have Mag 7 stocks in my portfolio because 1) they do not fall within any of the six target sectors where I exclusively invest, and 2) they generally do not meet my responsibility criteria. That is not to say you should or should not invest into these companies, by the way. This essay is about making your own decisions as to what is and is not responsible.

Regardless of what I think, many (maybe most) investment funds promoting themselves as responsible are invested in some or all of the Mag 7. For example, the top 5 positions in the aforementioned “Scored and Screened” index once known as the S&P 500 ESG Index are Mag 7 stocks. Had there been no Mag 7 titles in that index, it would have been beaten more than soundly by its big agnostic brother these past couple years.

About this responsible investing series

So far in this series, I’ve written a lot about background and, let’s say, investment preliminaries. In my next essay (number four), I will get closer to where the rubber meets the road, so to speak. I’ll discuss alternative approaches to getting started in responsible investing and about acquiring a requisite base of financial and investment knowledge. I hope you will join me for that. Also, if you have not yet read my previous essays in this series, I encourage you to go back and do so. If you’d like to be sure not to miss future articles in the series, please consider subscribing to this Substack or to our Channel BlueGreen at https://bluergreener.world/blog/ and/or follow us on one of our associated social media channels (Facebook, LinkedIn).

About the author: Gale A. Kirking is a Chartered Financial Analyst (CFA) and has earned the CFA Institute’s Certificate in ESG Investing. He formerly was employed as a senior equities analyst and director of investment research and has worked in and around the financial services sector for about 30 years. Kirking is not a licensed or registered financial adviser in any jurisdiction and does not make his living by providing financial advice. This essay and series are not intended to provide specific investment advice targeted or tailored to the needs of any individual investor. The views expressed herein are the opinions of the author. Other equally or more knowledgeable people will have different views.